Video

Understanding Steven Soderbergh. Part 3.

On two previews posts (Part 1 and Part 2) I wrote about the career of Steven Soderbergh. I also discussed his preference for working with small crews and even smaller gear, including shooting TWO movies with an iPhone.

On this third (and last) article I’ll share the gear, schedule and workflow he used the the Cinemax series The Knick. Why should I and other filmmakers care? Simple because I believe Soderbergh’s production approach will be the way how many TV shows and features will be produced from now on.

The 1 Person Crew.

Steven Soderbergh not only directed all 20 hour-long episodes of The Knick‘s first and second seasons, doing 70 setups the first day.

Doing a quick math, Soderbergh produced, directed, shoot and edited each complete hour-long TV episode in 7 days. Just as a reference, the industry’s standard is 10 to 14 days per episode and 150 days for a 2-hour big-budget feature film.

“The Knick is easily one of the most lushly crafted shows on television: beautiful cinematography, smart editing, and just the right balance of suspense and action.”

Wired Magazine

The Knick’s (incredible) production schedule.

Shooting started at 9 AM. While the crew had one hour off for lunch, SSDs with the morning’s footage were being downloaded and backed up. After lunch they kept shooting until 6 PM.

On his way home, Soderbergh edited the day’s footage, on a laptop, and was done by 8 PM. He then posted the footage (edited scenes, not dailies) on a password-protected website for the crew to watch and review. Then he went out for dinner with his wife.

Just like that.

Again, this isn’t new for Soderbergh. He’s been mastering his workflows to perfection. For HBO’s political satire K Street each 1-hour episode was plotted, scripted, shot, cut, and broadcast in five days.

How is this even possible?

I have a few thoughts:

- An essential aspect of Soderbergh’s approach is that he thinks like an editor while he’s shooting, never wasting time on anything he won’t use.

- Soderbergh has streamlined his production schedule to perfection. Two examples: the focus puller is in another room working wirelessly, freeing Soderbergh to concentrate on movement and framing.

- The sets are lit with practical lights (desk lamps, chandeliers, etc) so the actors can move anywhere they want and still be properly lit.

- Most set-ups shot in one day: 60. Least number of set-ups shot in one day: 10.

- Such crazy run-and-gun pace doesn’t allow time for elaborated compositions, but Soderbergh makes up for it with a fluid camera that often takes an unexpected perspective.

- Amount of locations where the entire principal cast worked together: one.

- Soderbergh always works with the same crew, developing short hands and perfecting their workflows on every project. For example, Gregory Jacobs, The Knick‘s executive producer, has collaborated on more than 20 projects with Soderbergh over the past 20 years.

Soderbergh’s Gear

The Knick was shot 6K HD (5:1 compression) on Zeiss Super Speed (35mm, 50mm, 85mm, all f/1.5), and an old RED 50-150mm f/2.8.

The total number of set ups was 2081 (roughly 28.5 per day). Out of those 2081, 577 were shot on an 18mm lens.

The show was shot almost entirely at ISO 1280 for texture, and almost always wide open at T1.3 for cinematic depth, often using NDs on interiors.

No DIT and no monitors on set with the exception on the 7″ RED on-board for operator/AC, and only two 17″ Sony OLED’s (one for each AC to pull focus via wireless video via these Teradek transmitters.

The Knick’s Post-Production schedule.

In terms of post-production, The Knick’s first season, Soderbergh spent “465 hours, 30 minutes, and 50 seconds” editing ten hour-long episodes, so that’s roughly 47 hours per episode.

- No editing on Monday nights because that day’s footage usually wasn’t fully downloaded.

- Tuesday night cut Monday’s material and first half of Tuesday if it was ready.

- Wednesday night cut Tuesday’s footage and first half of Wednesday.

- Thursday night cut Wednesday and first half of Thursday.

- No editing on Friday nights.

- Saturday and Sunday finish editing whatever was left from the end of the week.

“Edited footage gives a much clearer indication of directorial intent and also prepping, posting, and watching all the dailies is a pain-in-the-ass time-waster. Optimization of process is not just my goal, it’s something of an obsession.”

Steven Soderbergh

Final Thoughts

There are less and less directors doing a complete series, and even less fulfilling multiple roles on a single production. I personally believe most projects would benefit by having a unifying visual language throughout.

I believe Soderbergh’s production approach will be the way how many TV shows, shorts and even features will be produced from now on. Stay tuned.

Video

Understanding Steven Soderbergh. Part 2.

On my previous post I wrote about Steven Soderbergh’s professional life. The goal was to give some context on why I consider him a leading force in the future of filmmaking, regardless the quality or financial success of his most recent movies.

I started paying close attention to how Steven Soderbergh works around 2014 when he released the Cinemax show The Knick.

On this post (and the next one) I’ll share everything I know on Soderbergh’s production schedule, using the iPhone to shoot Unsane and High Flying Bird, his approach to scriptwriting, and why he prefers working with skeleton crews.

The huge advantages of small crews.

Let’s start with that last part. By now you know I prefer to shoot with the smallest possible crew and the least amount of gear. So much so that I recently started a new website called the 1 Person Crew. There I shared why Robert Rodriguez is also one of my heroes. But here’s Steven Soderbergh’s take on the advantages of working lean and mean:

“One of my favorite shooting days on High Flying Bird was when we did the opening scene at The Standard hotel. We took a break, and then we started walking downtown New York with a crew of four or five people, and André. I’m walking and I’ll go, “Okay, stop, we’ll put the camera here.” Shoot that, walk, walk, walk, okay, we’re stopping here. It was really fun. It took us two hours to walk and shoot our way down to the World Trade Center.”

Steven Soderbergh

Steven Soderbergh’s iPhone

“‘I don’t want to wait on the tool, the tool should wait on me.”

Steven Soderbergh quoting Orson Welles.

High Flying Bird and Soderbergh’s previous movie Unsane were shot on an Apple iPhone. It’s all about size, and the ability to get the shot he wants in tight quarters. In Unsane when space got particularly tight, Soderbergh would just tape the iPhone to the wall to get the frame he wanted.

The visuals are harsh and uncompromising, but Soderbergh sees that as part of the appeal. Unsane is a great worst-nightmare movie, a tense piece of low-budget auteurship that plops the viewer into an absurd scenario and then ratchets up the tension for the next 90 minutes.”

The Atlantic

For “High Flying Bird” Soderbergh originally wanted to shoot anamorphic, and have a much cleaner, slicker look. But the challenge was gaining access to real-life locations that embodied an affluent world. For a small, nimble production, the advantages of the iPhone outweighed the image fidelity of an ARRI or RED cameras that cost a hundred times more.

“The iPhone seemed to me a pretty natural fit for that approach. It still is, in my mind, in terms of the scale of it, the speed that was necessary to execute it, in the time we had allotted.”

Steven Soderbergh

On High Flying Bird there’s a shot where three actors are walking down an office corridor. As all three break in different directions the camera follows one actor into an office, and then retreats.

A 350-pounds dolly? Screw that! Instead, Soderbergh sat in a wheelchair, holding the iPhone on this tiny Gimbal mimicking a mini crane movement.

“Using a more traditional approach with normal-size cameras would have been extremely difficult, if not impossible. To get the lens where I wanted, to be moving in certain way or have the camera reach multiple destinations without either somebody getting hurt, or the shot being compromised because of the size of the equipment. A normal size dolly, weighs 350 pounds. Moving quickly can be dangerous and somebody could get hurt. And we could have been there for hours.”

Steven Soderbergh

“I get very frustrated when it takes a long time to execute it. Like, as soon as I feel it, I want to shoot it. And so, that’s one of the biggest benefits of this method — the time from the idea to seeing an iteration of it is incredibly short, like, a minute, like, maybe less. For me, the energy that that creates on set, and I think on screen, is huge.”

Steven Soderbergh

Soderbergh’s lighting package (shooting with the iPhone or proper cinema cameras) has been stripped down to a 12-inch by 12-inch LED panel (like this) in recent years. The look can be more evocative of a filmmaking student than an Oscar-winning director with 30 features under his belt. But this is as much an aesthetic as a practical decision, especially since 2000 when Soderbergh took over the cinematographer’s role on his films.

From Script to Screen.

The Knick’s original script called for 10 episodes. Instead of working on complete episodes one at a time Soderbergh turned the script into a “10-hour movie” shooting the first season in 73 days. In other words, Soderbergh shoot eight to nine script pages a day, double the typical rate for a TV drama. This wasn’t a new approach for him. Back in 2003 each episode for K Street was plotted, scripted, shot, cut, and broadcast in five days. Same exact story for the 2017 Netflix series Godless.

“The original script for Godless was 175 pages. Instead of chopping one of its limbs off, we thought “why don’t we turn this into a series?” So we approached Netflix with the idea and they said “Go. You’re starting tomorrow. Netflix ability to move that quickly and that definitively is their biggest advantage.”

Steven Soderbergh

On my next post I’ll share the gear, schedule and workflow Soderbergh used the the Cinemax series The Knick, and why I believe his production approach will be the way how many TV shows and features will be produced from now on.

Video

Understanding Steven Soderbergh. Part 1.

Today I’d like to share a bit about Steven Soderbergh’s professional life, and why have I’ve been following him for years. On two upcoming posts I’ll share everything I know about his working methods, including his shooting schedule and preferred workflow and gear. Cool? Let’s go!

Thirty years ago Steven Soderbergh became the pioneer of independent cinema with his first movie Sex, Lies and Videotape. Today he leads the future of filmmaking and might be even shaping the future of the NBA.

Last week, Steven Soderbergh’s latest film “High Flying Bird” launched globally on Netflix. I waited for weeks to watch it and… let’s say it wasn’t exactly what I was expecting.

To be fair, I don’t follow professional sports, and the film is about an NBA agent and a rising basketball star who try to change the business of professional basketball. With only 72 hours to pull off a daring plan, they try to outmaneuver the other players with a strategy that could change the game forever. The outcome raises questions of who owns , and who should own, the game.

Interestingly, the characters in “High Flying Bird” imagine what could happen if pro players took their careers into their own hands using the power of the internet. Well, that is EXACTLY what Steven Soderbergh has been doing with the Hollywood studio system for a very long time.

For example, back in 2005 (before anyone thought is was possible) Soderbergh released Bubble simultaneously in theaters and as a home release. In 2009 he tried the same approach with The Girlfriend Experience with adult film star Sasha Grey.

In 2017 with Logan Lucky, Soderbergh

“crafted a project that bypassed traditional Hollywood production and marketing formulas, targeted his advertising to find the right audience, edited trailers himself, and ignored the usual branding paradigms.”

The Atlantic

Who is Steven Soderbergh?

He is the guy who once directed Out of Sight, The Limey, Erin Brockovich, Traffic, and Ocean’s Eleven, all within a three-year period.

Many people forget (or don’t know) that in 2000, Soderbergh received two Oscar nominations for Best Picture, and won Best Director for Traffic.

As of right this second, Soderbergh has 42 credits as director, 49 as producer, 28 as cinematographer and 23 as editor. He has 28 features and over 30 hours of TV series. His directorial work alone have grossed over US$2.2 billion worldwide.

“Soderbergh has worked in every genre and at all levels of the studio system. He directed glossy franchise entertainment (Ocean’s Eleven), Oscar-winning successes (Traffic and Erin Brockovich), hard-boiled noirs (Out of Sight and The Limey), and low-budget experiments (Full Frontal, Schizopolis, and The Girlfriend Experience).”

The Atlantic

In other words, Steven Soderbergh is not a human from planet earth.

Steven Soderbergh’s Oscars Acceptance Speech.

“There are a lot of people to thank. Rather than thank some of them publicly, I think I’ll thank all of them privately. What I want to say is — I want to thank anyone who spends part of their day creating. I don’t care if it’s a book, a film, a painting, a dance, a piece of theater, a piece of music… Anybody who spends part of their day sharing their experience with us. I think this world would be unlivable without art, and I thank you. That includes the Academy. That includes my fellow nominees here tonight. Thank you for inspiring me. Thank you for this.”

Steven Soderbergh

That’s a powerful message. So powerful that the Academy Awards recently held it as “the ideal of an Oscar speech” probably because it is short and to the point.

The real-life story behind the speech is fascinating:

“I had nothing prepared because I knew I wasn’t going to win. I figured Ridley Scott, Ang Lee, or Stephen Daldry would win. So I was hitting the bar pretty hard, having a great night, feeling super relaxed because I didn’t have to get up there.”

Steven Soderbergh

So the combination of lots of alcohol and lack of preparation worked well that night. Going back to Soderbergh’s professional life,

On Marketing Logan Lucky.

“Logan Lucky was released on August because historically, it has been a good time to release something of quality. There’s typically a dead zone before Labor Day. The big summer movies have played out, and there are three weeks with some breathing room. You just need a lot of marketing money, more than we had. I was aware it might not work. I learned a lot, and it was absolutely a worthwhile thing to do, to try and create an avenue for projects that don’t fall in any of these tiers or to want to have creative control over everything, with more financial transparency.”

Steven Soderbergh

On my next two post the plan is to share everything I know on Soderbergh’s production schedule, his approach to scriptwriting, and why he prefers working with skeleton crews.

Video

Upcoming workshops at NAB.

I’m very happy to announce that I’ll be speaking at the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) in April.

NAB has been held since 1991 at the Las Vegas Convention Center in Las Vegas, Nevada, and this is my 12th year in a row speaking at the show!

A couple of years ago NAB had 103,000 attendees from 161 countries and more than 1,806 exhibitors. In other words, it is HUGE.

CONFIRMED EVENTS

The Future of Storytelling

Saturday, April 6, 2019

5:15-6:30pm | Social Media & Streaming Video Track

This session covers a variety of software applications and digital platforms, as well as new approaches to present multimedia content.

Direct link on NAB’s website

The 1 Person Crew Approach

Monday, April 8, 2019

2:00-3:15pm | Production Track

This session provides valuable insights on planning, shooting, and producing video projects, while working with very small crews and shoestring budgets.

Direct link on NAB’s website

More info about the 1 Person Crew approach

Production for Small Crews and Budgets

Wednesday, April 10, 2019:

2:00-3:15pm | Production Track

Attendees are exposed to a wide variety of pre-production aspects including scripts, storyboard, and location scouting apps, and key questions to ask clients.

Direct link on NAB’s website

Pre-Production Course on Lynda.com

Post-Production Course on Lynda.com

Video

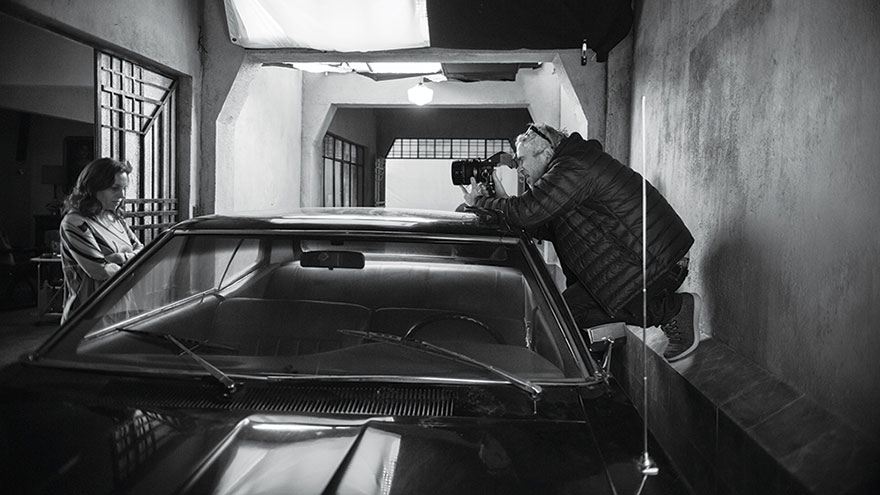

The Sound of Roma.

I started thinking about a “Roma” blog post a few minutes into the movie.

Why Black and White? What do those almost endless pans mean? How similar or different is the composition compared to “Gravity“? What’s the meaning of “water” for Cuaron?

But as I started reading more about the movie, which by the way was written, directed, produced, shot, and co-edited by Alfonso Cuarón, my attention quickly drifted to the film’s sound design.

First things first.

I am assuming you know about Roma. If you don’t, here’s the executive version. Roma is a semi-autobiographical take on Cuarón’s childhood in Mexico City in the early 70’s.

So far Roma has won the Golden Lion in Venice, received 10 nominations at the 91st Academy Awards—including Best Picture, Best Foreign Language Film, Best Director, Best Actress and Best Supporting Actress. It is tied with The Favourite as the most-nominated film, and with Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) for the most Oscar nominations ever received by a film not in the English language.

It also won Best Director and Best Foreign Language Film at the 76th Golden Globe Awards, Best Director and Best Picture at the 24th Critics’ Choice Awards, and at the 72nd British Academy Film Awards won Best Film, Best Film Not in the English Language, Best Direction and Best Cinematography.

UPDATE 20190225: Roma delivered Netflix its highest Oscars prestige yet, contending in 10 Academy Award categories, and wining three: Best Director, Foreign Language Film and Best Cinematography. Alfonso Cuaron gave Mexico its first foreign language film Oscar.

Sound Design.

Now, back to sound design. So it happens, the sound supervisor and re-recording mixer was the Academy Award-winning Skip Lievsay, who also worked on “Gravity“, “Children of Men“, “Y Tu Mama Tambien” and all 18 movies by the Cohen Brothers.

The most informative resource was this interview with Skip Lievsay on YouTube. Here are 3 of my favorite sections:

The full interview.

I highly recommend listening to the complete interview to learn:

- How not having a musical score keeps the audience guessing what will happen next

- Why it was important to Cuarón to have the dialog emanate not just from the screen channels but from all around the audience

- The stunning five-day loop group recording session with 350 actors

- How the final mix of the film took 10 weeks, 7 days a week, 12 hours a day.… wow…..

The technical stuff.

Filmmaker Magazine has another great article on Roma’s sound design. It’s a bit technical but enjoyable.

“In Atmos, we were able to use the x-axis and the y-axis as well as the z-axis. That’s the trick — using the z-axis in terms of extra reverbs or spatial ability.”

Filmmaker Magazine

A (much) deeper interpretation.

If you are interested in a more esoteric approach to Roma, pay close attention to these comments by another maestro, Guillermo del Toro.

Get 60 days FREE of the best music for filmmakers.

Get 30 days FREE of the best collaboration software.

Video

More Must-Read Books for Filmmakers.

Yesterday I shared my 20 favorite books on filmmaking and I received numerous emails saying “how come you didn’t include A” or “you can’t leave B out of the list!” So, by popular demand (literally) I’m adding a few more.

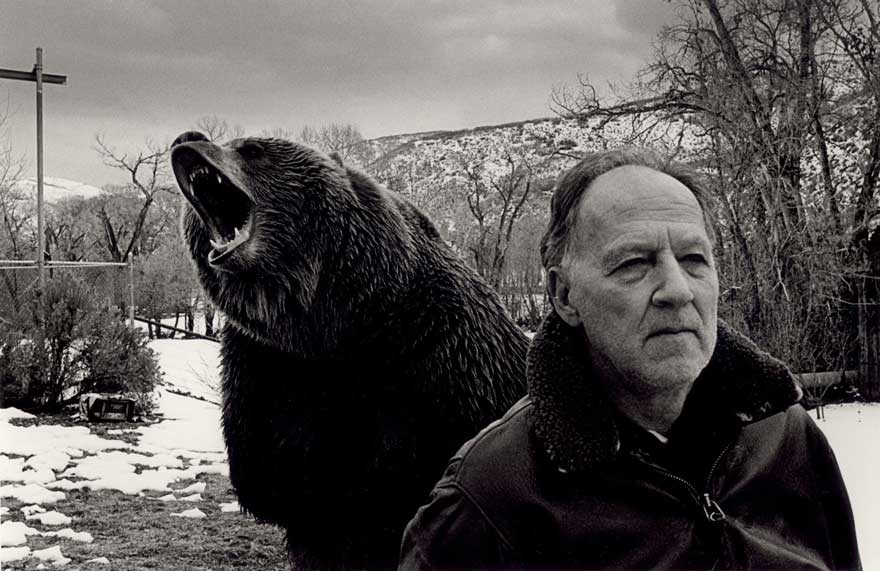

Let’s start the list with a non-technical book: “Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed” by Paul Cronin. I highlighted almost every page. Herzog provides SO much practical wisdom that I have gifted this book to at least 10 people so far, and I’m just getting started.

One of my goals this year is to get much better at grading. With current tools like the Lumetri Panel on Adobe Premiere Pro, or Davinci Resolve the excuses are over. The “Color Correction Handbook: Professional Techniques for Video and Cinema” by Alexis Van Hurkman is a dense, sometimes difficult book to follow, but it has all the information you might need to improve your color correction and grading skills. At almost 700 pages, I strongly suggest getting the digital version.

Christopher Kenworthy has authored not only one but TWO books I consider outstanding. I’d start with “100 Ways to Shoot Great Dialogue Scenes” and then get “Master Shots: 100 Advanced Camera Techniques to Get An Expensive Look on your Low Budget Movie.” Both are truly inspiring.

If you are interested in directing, Michael Rabiger’s “Directing: Film Techniques and Aesthetics” is very comprehensive. The book “explores how to discover your artistic identity, develop credible and compelling stories with your cast and crew, and become a storyteller with a distinctive voice and style.” I also like that there’s a companion website with additional teaching notes and practical hands-on projects.

Another good book for aspiring directors is “Shot by Shot: Visualizing from Concept to Screen” by Steven D. Katz. There’s a lot of good info, but the book is somewhat outdated.

I’m also very interested in editing, not necessarily to do it on every project but to have a better understanding of what my editor will, and will not, need. The more I learn about editing, the more efficient I am as a director of photography. There are three books I’d highly recommend on this topic (in order of preference): “Great Cuts Every Filmmaker and Movie Lover Must Know by Gael Chandler. Spend a few weeks mimicking every cut provided and you’d greatly enhance your understanding of the craft of editing.

My second pick would be “The Technique of Film and Video Editing: History, Theory, and Practice” by Ken Dancyger. Simply put “this isn’t a quick read but definitely worthwhile if you want to gain an understanding of what it takes to be an excellent director and editor.” Enough said.

My third pick would be “In the Blink of an Eye: A Perspective on Film Editing” by Walter Murch. This books seems to be on everyone’s favorite list.I always enjoy reading anything Murch, and this book is fun, but in all honesty I didn’t get much practical knowledge from it.

And last, but by no means least, a book about Sound: “Producing Great Sound for Film and Video” by Jay Rose. I just got this one for Christmas, but looking at the index, it promises a LOT of fun and exciting challenges.

What about you? Any favorite books?

Video

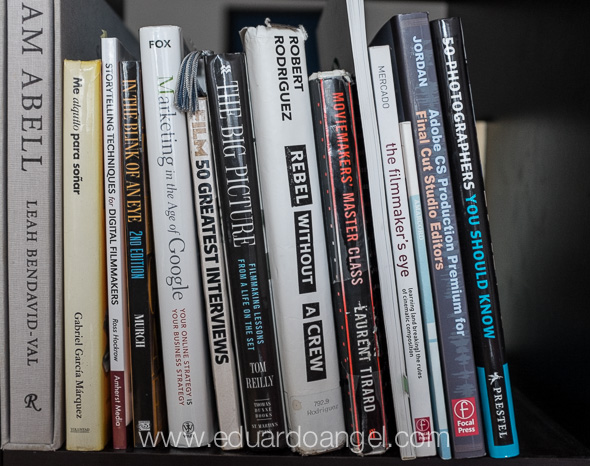

The 20 Best Books on Filmmaking.

Over the years I have been steadily collecting the best books on filmmaking. Most of these titles have been thoughtfully recommended by friends and students. A few have been fortuitous purchases inspired by intriguing reviews found on Amazon. And, of course, there are some that have come to find a home on my bookshelf in other mysterious ways.

1. The Oxford History of World Cinema by Edward O’Neill

“This is NOT a Summer reading book. Over 800 pages and (4 pounds), this one is perfect for rainy afternoons while sipping coffee and dreaming away.”

2. In the Blink of an Eye Revised 2nd Edition by Walter Murch

“One of my favorite and most inspiring books. Anyone interested in video editing, sound design, directing or screenwriting should buy this book immediately.”

3. MasterShots 100 Advanced Camera Techniques to Get an Expensive Look on Your Low-Budget Movie by Christopher Kenworthy

“Effective camera techniques to increase the production value of your productions.”

4. The Filmmaker’s Eye: Learning (and Breaking) the Rules of Cinematic Composition by Gustavo Mercado

“Understanding the rules of cinematography and how to successfully break them.”

5. Directing: Film Techniques and Aesthetics by Michael Rabiger

“An interesting approach (from a director’s persepctive) to script analysis and development.”

6. The Color Correction Handbook: Professional Techniques for Video and Cinema by Alexis Van Hurkman

“Grading is such an important aspect of post-production that understanding the possibilities, and limitations, is key.”

7. The Technique of Film and Video Editing: History, Theory, and Practice by Ken Dancyger

“A “precise look at the artistic and aesthetic principles and practices of editing for both picture and sound.””

8. Rebel without a Crew: Or How a 23-Year-Old Filmmaker With $7,000 Became a Hollywood Player by Robert Rodriguez

“A true inspiration to “stop dreaming and start doing.””

9. Cutting Rhythms: Shaping the Film Edit by Karen Pearlman

“There are so many ways to cut and present a story. Understanding the right “rhythm” of each story is an essential skill.”

10. The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film by Michael Ondaatje

“Would you pay $20 to hang out with the editor behind “American Graffiti” “The Conversation,” “Apocalypse Now,” “The Godfather,” “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” and “The English Patient?”

Then buy this book.”

11. The Five C’s of Cinematography: Motion Picture Filming Techniques by Joseph V. Mascelli

“First published in 1965 this classic is now more relevant than ever. My go-to textbook on all my Filmmaking Workshops.”

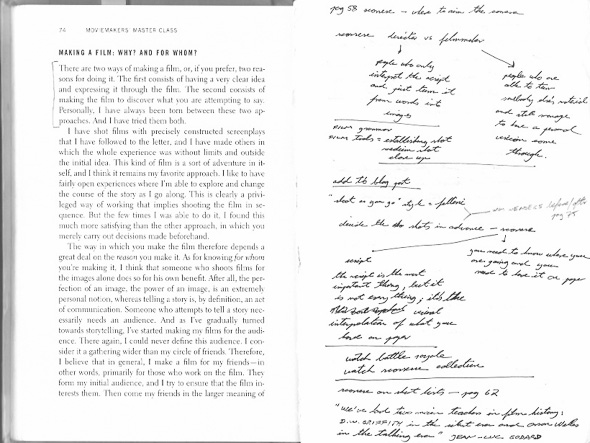

12. Moviemakers’ Master Class: Private Lessons from the World’s Foremost Directors by Laurent Tirard

“Witness the thought process behind Almodovar, Bertolucci, David Lynch, the Coen Brothers, John Woo and Woody Allen. Their processes are all very different and all very effective.”

13. Guillermo del Toro Cabinet of Curiosities: My Notebooks, Collections, and Other Obsessions by Guillermo del Toro

“Guillermo del Toro’s notebook, the genius behind Hellboy, The Orphanage, and Pan’s Labyrinth. Foreword by James Cameron, afterword by Tom Cruise, and contributions from Neil Gaiman and John Landis, among others.”

14. Cinematography: Theory and Practice: Image Making for Cinematographers and Directors by Blain Brown

“Getting this book and Amazon’s Instant Video is like getting an MFA in Cinematography.”

15. The Big Picture: Filmmaking Lessons from a Life on the Set by Tom Reilly

“The book covers 50 short, to the point, extremely useful tips that have helped us save an incredibly amount of time and money on pre-production and production. This book is a fantastic resource.”

16. The Philosophy of the Coen Brothers by Mark T. Conard

“A book about the Coen Brothers. Enough said.”

17. Directing Actors: Creating Memorable Performances for Film & Television by Judith Weston

“Understanding the technical aspects of filmmaking is as important as learning how to communicate with the people you work with, especially when they are NOT professional actors.”

18. Hitchcock (Revised Edition) by Francois Truffaut

“Simply put, this is a book-length conversation between two of the best film directors in history.”

19. The Complete Film Production Handbook by Eve Light Honthaner

“Everything you need to know to set up and run a production. An essential resource if/when you need to work and communicate with much more experienced producers.”

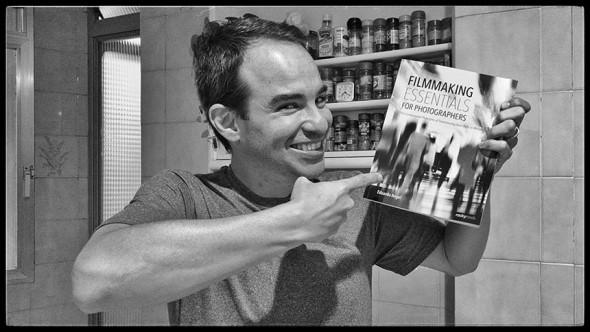

20.Filmmaking Essentials for Photographers: The Fundamental Principles of Transitioning from Stills to Motion by Eduardo Angel (yes, that would be me!) UPDATE: The PDF version is now available here.

To remain relevant and in demand in today’s visually driven world, image makers must learn to craft both still photographs and motion in order to attract clients. While there are many similarities between photography and cinematography, there are key aspects of shooting motion—such as sound and camera movement, to name just two—that are uncharted territory for most photographers.

These are books that I own, have read multiple times, truly enjoy, and highly recommend. My hope is that they help you sharpen your skills, improve your craft, and give you many hours of joy and wonder.

Here’s the complete list on Amazon.com: my top 20 favorite books on filmmaking.