Video

Upgrading from HD to 4K. Worth it?

There are currently 2.7 billion active smartphones in the world. An estimated 800 million were added this year alone. By 2020, Ericsson predicts there will be at least 6.1 billion smartphone subscriptions globally. What’s the big deal? Well, this means 38% of the world’s population has the ability to shoot digital video and stills.

That is not very good news for us as content providers.

The way I see it is that we need to diversify our professional skills, learn as much as we can, learn how to edit, how to grade, how to record better sound, and how to tell more engaging stories. In an ever-changing marketplace, the more you know the safer you are.

Smartphones aren’t the only problem though. The average price of professional editing software went down from $1,300 to $299 in the past 10 years, and this is an average that includes high-end apps like Avid ($1,300) and excellent software applications like Blackmagic’s DaVinci Resolve, which “Lite” version is completely free.

The cost of a cinema-quality camera tumbled from $200,000 in 2001 to $1,000 today.

Photography and film students with current DSLRs have way more resolution and features than any $200,000 camera from 10 years ago. This is incredible!

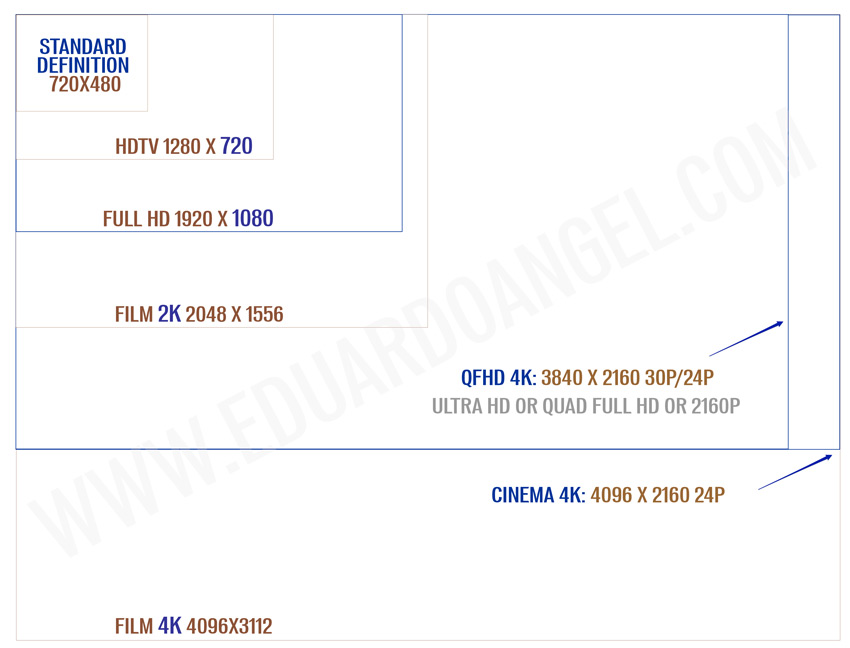

Before I started shooting 4K I didn’t really know what all the fuss was about. Then I put this chart together. For some of you this might be pretty obvious, but it can’t hurt to check it out.

Is upgrading from full HD to 4K worth it? You would think this would be one of the main questions I encounter, but last year at NAB I was absolutely shocked to find out that many companies, mostly broadcast stations, are still shooting SD and that they are now considering making the jump straight into 4K. That’s a pretty big jump, but for some of them it can make a lot of sense.

Should you do it? It depends. Think 35mm digital cameras vs. medium format digital backs. Phase One vs. Canon or Hasselblad vs. Nikon. Most advantages and disadvantages regarding sensor sizes, file sizes, shooting speeds, portability, and especially storage and post-production challenges apply. Except for price. For $2,500 we can now capture 4K RAW or almost literally in the dark. For $1,300 we can record HD slow-mo or 4K internally. And for $500 we can shoot 4K anywhere.

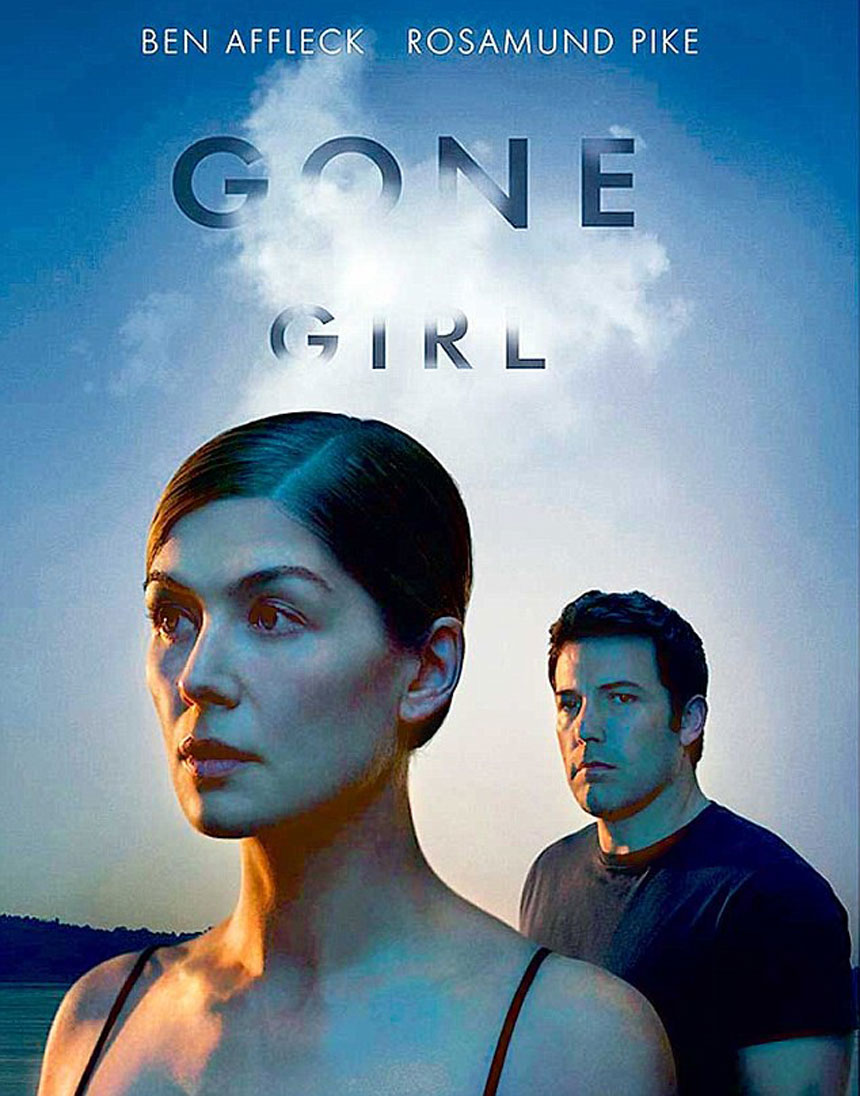

These systems are so inexpensive that they sometimes become a double-edged sword. Their sizes and prices transform them into accessible toys. And that’s where the problems start. Higher resolution often demands new workflow requirements. In RAW form, a 2.5-hour movie shot in 4K at 24fps contains 216,000 frames. The resulting file is approximately 5.6 terabytes of data. That’s ONE camera, BEFORE back ups. But who really shoots that way? Well, David Fincher shot 500 hours of 6K RAW with multiple RED Dragon cameras for his latest movie “Gone Girl.” The end result was 315 terabytes of footage. Crazy? It depends, for normal people with normal budgets, yes. But Fincher was dealing with a time crunch and had to release many actors as fast as possible, so they shot many scenes in loose medium shots and zoomed in and reframed them in post when needed.

I don’t believe 4K UHD is another fancy trend or marketing gimmick to make us spend our hard earned dollars on something that will become obsolete before the year’s end (3D anyone?). I truly see 4K UHD as a natural transition, or evolutionary step, in screen resolution. In 2015 I expect to see many more new models of 4K UHD TV sets than new models of 1080p HD TVs.

This doesn’t mean everything is safe and sound and all the potential issues have been ironed out. For example, a recurrent question I get at all my presentations is “what’s the best way to distribute 4K?” and the answer is far from perfect, as we currently have very limited options.

Let’s take Blu-Ray for example. A Blu-Ray disc can fit 25 GB per layer. A 2K film takes 50 GB, so that technology is currently maxed out. The good news is that as of last September, the Blu-Ray Association announced it would support 4K video at 60 fps, High Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC), and 10-bit color depth. According to this association, the new generation of 4K Blu-Ray disks will have a data rate of at least 50 Mbit/s and may include support for 66/100 GB discs. Awesome!

4K UHD Blu-ray players are being developed in conjunction with the UHD alliance, comprising manufacturers such as Samsung and Panasonic, as well as movie-industry players such as Technicolor, 20th Century Fox, and Warner Brothers. The alliance is not only responsible for establishing standards with regards to specs like 10-bit color and High Dynamic Range (HDR), but also for pushing content creation forward and managing distribution.

The huge appeal of HEVC (High Efficiency Video Coding) is that it essentially doubles the data compression ratio while keeping the same level of video quality and it can support 8K UHD with resolutions up to 8192×4320. I want to think that 8K is extremely far off in the future, and that it will be a very long time before we need such resolutions. But, I (sadly) still remember when a 100MB zip drive seemed impossibly huge and we debated if putting all your assets on a 1GB Microdrive was practical or even irresponsible.

As we all know, both the iPhone 6, and iPhone 6 Plus support HEVC/H.265 for FaceTime. Recently, Microsoft confirmed that Windows 10 will support HEVC out of the box, and DivX developers announced that DivX265 version 1.4.21 has added support for the Main 10 profile of HEVC and the Rec. 2020 color space. Online streaming might also seem like a great solution, but not yet. Netflix recommends a minimum download speed of 5MB for 720p, 7MB for a 1080p and 12MB for 3D movies and a whooping 25MB for 4K.

What’s wrong with this picture? I have a dedicated “business” internet plan. The fastest, and obviously most expensive plan I can get in my area. My download speed is less than 17 MBps, not nearly enough for Ultra HD quality, so broadband speeds will need to increase and prices will have to come down if the interested parties really want 4K to be widely accepted by movie buffs, sports fans, and especially gamers.

A nice advantage of 4K UHD TV sets is that they are backwards compatible, which means that they will work fine with your existing DVD and Blu-Ray players, as well as satellite and cable boxes. They can also “upscale” HD content and display it as best as possible. This past summer some of the FIFA World Cup games were broadcast in 4K. I watched a couple and it was a surreal experience. From certain angles, like shots from the sidelines, it felt almost like physically being in the stadium. The most popular VOD providers like Netflix and Amazon, major cable companies like Comcast and DirectTV, Hollywood studios, YouTube, and even local TV news station are starting to deliver 4K content, so hopefully other services will follow suit. What’s next? Streaming 4K media from a smartphone to an HDTV.

We increasingly have access to very powerful and generally cheaper tools. But tools are just that. When to choose one over another and, most importantly, why it should be chosen are the real questions. Here’s something interesting; Ophthalmologists generally agree that the higher the resolution of your monitor, the better it is for your eyes. Why? Because (according to them) the text looks sharper, and at a certain point, the pixels are so small your brain can’t tell it’s not looking at real stuff. Exciting or sad. Up to you.

Cool Links on 4K:

4K Camera Workflows- Raw, Video, Proxy

Nearly 50% of Video Professionals in UK Never Saw 4K

Netflix to Begin Charging More for 4K Streaming

How 4K Benefits Videographers and Photographers

What 4K means for post production

What Is 4K Video? A Guide to the Rising Industry Standard

The Pros and Cons of Shooting News Footage in 4K

The Wall Street Journal goes 4K video with the GH4

Video

In the Mood for Love Redux.

I love Asian cinema and I feel a strong and special attraction and respect for Wong Kar-Wai’s work, especially his earlier collaborations with Chris Doyle. Wong Kar-Wai is known for his “romantic and stylish films that explore—in saturated, cinematic scenes—themes of love, longing, and the burden of memory.” In terms of photographing urban landscapes, especially at night, I can’t think of a better cinematographer than Doyle.

For the past couple of months I’ve been revisiting his movies, his video interviews, and reading as much as possible about his production methods and unconventional approaches to filmmaking.

Check out the following books to learn more about this amazing director:

“The Sensuous Cinema of Wong Kar-Wai” by Gary Bettinson

“Wong Kar-Wai: Auteur of Time” by Stephen Teo

“Wong Kar-Wai” by Peter Brunette

The long-awaited and complete Kar-Wai retrospective with more than 250 photographs and film stills will be released in September but it can be can pre-ordered now.

In order to better understand his compositional and directorial choices I imported “In the Mood for Love” into Premiere Pro and selected my favorite scenes, including those critical to the story, those that are brilliantly original, and scenes that are flawlessly executed or contain a number of technical achievements (like the impeccable use of dolly moves). I then re-cut all my favorite scenes from the original 94 minutes into a single 18-minute clip (below), always trying to keep the integrity of the story. My goal here is to help someone who hasn’t seen the movie grasp its (very convoluted) story in one 18-minute clip.

If you haven’t see the movie, I highly recommend it, and I’d love to hear from you once you see it.

If you have seen the movie, did I leave any key cinematic moments out?

Video

The eternal quest for “the best” digital camera.

I often receive emails asking for advice about “the best lens” or “the best camera” or even “the best laptop.” I believe it is simply impossible to determine a “best” of anything as there are too many random factors such as experience, budget, expected lifetime of the product, intended use, availability of accessories (like lenses or batteries), and even tech support in certain areas. That’s not even considering more subjective factors like personal preference, sense of loyalty to certain brands (or dislike for others), and even the size or weight of such tools. Interestingly, we are currently experiencing one of those “what’s the best” dilemmas ourselves, and not a minor one by any means; we are reconsidering our standard camera package for 2015–16.

Renting vs. Owning:

For many reasons, I believe renting is one of the best options for most people. When all you have is a hammer, the solution to every problem requires a hammer. That’s a very limiting factor to your creativity and a disservice to clients. Sometimes you can get the job done with a Swiss Army Knife like MacGyver, sometimes you need a nice toolbox, and sometimes the best approach is to have a professional plumber do the job.

Another huge reason to rent is to keep overhead as low as possible. Unless you are shooting several times a week with the same system, having something that is guaranteed to quickly decrease in value simply collecting dust in a drawer isn’t the best financial move. Unfortunately, renting is not an easy or affordable option in many small cities.

Lenses:

In terms of lenses I own a nice selection (from 8mm all the way to 200mm) of mostly Canon L glass, some Sigma ART lenses (with Canon mounts), as well as a couple of Panasonic Lumix lenses. I also have one Metabones Speedbooster adapter (Canon EOS to MFT).

Accessories:

We own a set of LED lights and basic accessories that I use frequently and will last a long time like monopods, tripods and a few camera movement tools. I also own a complete audio kit simply because we use it quite often. Audio tools tend to be fragile, and we have a very specific preference for brands and settings. Ultimately, because sound is such an important element of any video project, completely trusting it gives me an additional peace of mind. But I digress. The point of this article is not audio equipment, but cameras.

Cameras:

We own a Panasonic Lumix GH4 bodies and still have a couple of GH3 bodies. They have served me extremely well on hybrid assignments. I am very happy with the quality of the footage and always having the option to shoot 4K, HD, built-in slow-motion, and time lapses with the same camera and media. For video-only productions we usually rent Canon C100 Mark II or C300 Mark II bodies, which I also like very much.

The Challenge:

Several upcoming projects will require a more “complete” camera package, and we seem to have enough projects in the pipeline that it might make sense to own instead of rent, not only financially, but to save time picking up/returning and to be certain that the tool we plan on having in pre-production is the same tool we use on location weeks or months later. So, what’s the best cinema camera (for us) right now?

Technically speaking, we will need a main camera (Cam A) that ideally shoots 4K and has all the standard bells and whistles like XLR ports, HDMI, a good viewfinder, variable frame rates, peaking, ND filters, etc. Great low-light performance is key. For several projects we’ll need to shoot high-quality behind the scenes footage, so we will need a second camera (Cam B) that is either the same or very close to the quality of Cam A.

To make the riddle even more interesting, some of these projects will be “hybrid” projects that require on-location, mostly unplanned, and available light shooting with a very small crew (two or three people max). So the gear package needs to deliver great stills, great footage, and be easily operated by one person, which means light and compact.

Possible Solutions:

I will only discuss the main components of the package, so additional batteries, cables, memory cards won’t be included in the total price.

1. Canon

The first and obvious move would be to buy a couple of Canon C100 Mark II bodies. We already know and like the system, and own the lenses, so there’s no need for adapters. Unfortunately the C100 Mark II does not offer 4K, it is good but not great in low-light performance, it is small but not super light or compact, and it does not shoot stills, so I’ll need to get a Canon EOS 5D Mark III or at the very least a Canon EOS 70D. I’ll get the cinema features I need on only one of the systems.

1x Canon C100 Mark II = $5,500 (Amazon • Adorama)

1x Canon EOS 70D = $900 (Amazon • Adorama)

Total = $6,400

2. Sony

The second option would be to get a Sony FS7 AND a Sony a7S as a B Cam (and also for stills and BTS). The first one seems to be the new cool kid on the block, with raving fans and over the top reviews. It seems portable enough for a cinema camera and matches most of our technical requirements (I still need to test the low-light performance). Its little sister, the a7S shares the same outstanding reviews, it is clearly number one in low-light performance and it can even capture 4K to an external recorder. The catch, and this is a big one, is the cost. The FS7 goes for $8,000 and the a7S goes for $2,500. In order to use my existing lenses I’ll need two Metabones Speedbooster adapters (Canon EOS to NEX) at $650 each, but I will not have AF capabilities when shooting stills, which is a major issue. Also, in order to fully use the a7S as the B Camera we probably would need an Atomos Shogun adding a lot to the budget.

1x Sony FS7 $8,000 (Amazon • Adorama)

1x Sony a7S $2,500 (Amazon • Adorama)

2x Metabones adapter (Canon EOS to NEX) $800 (Amazon • Adorama)

1x Atomos Shogun $2,000 (Amazon • Adorama)

Total = 13,300

3. Panasonic

A third, and more affordable option would be to get a second Panasonic Lumix GH4 body and keep them as A Cam and B Cam (4K, HD, and stills) and something like the Panasonic HC-X1000 as a C Cam for BTS. I am still missing the “standard bells and whistles” I mentioned above, and I still have to test the X1000’s performance under low-light. Getting the YAGH (“brick”) wouldn’t make much sense in terms of money, size, weight, and additional power sources.

1x Panasonic Lumix GH4 $1,500 (Amazon • Adorama)

1x Metabones Speedbooster adapter (Canon EOS to MFT) $600 (Adorama)

1x Panasonic HC-X1000 Camcorder $3,200 (Amazon • Adorama)

Total: $5,300

4. Blackmagic

We briefly considered Blackmagic systems but found too many cons to even add them here. Another topic for another day.

Conclusions:

Honestly, there aren’t any. Not yet, anyway. We are still trying to figure out what to do. The Panasonic Package (#3) is the cheapest and easiest as we would have a very small learning curve (with the HC-X-1000) but low-light performance remains to be seen (and it is good but not great on the GH4). The price is great but we would only have the cinema features we need in one of the three cameras.

The Canon Package (#1) is right in the middle, but we would lack 4K, slow motion, a codec over 50mb/s, and only one of the two cameras offers the bells and whistles we are looking for.

Sony (#2) seems to offer the best solution, but costs twice as much as Option #1 and $8,000 more than Option #3. We would lack autofocus for stills, only one camera will have the cinema features, and the FS7 could require a significant learning curve.

An alternative, suggested by an experienced filmmaker, would be to keep using our GH3 with the Panasonic lenses as our stills camera ($0), use the GH4 with our Metabones and Canon and Sigma glass as Camera B, and simply buy one Sony FS7 ($8,000) and a second Metabones (Canon EOS to NEX) adapter $400 for a total investment of $8,400. Altogether we would get AF for stills, 4K, slow-mo, no need for new lenses, but only OK low-light performance, and only ONE system with XLR ports, ND filters, etc. I am also seriously concerned with the additional time (and expense) in post to make everything look somewhat close.

Money and lenses are obviously very important considerations, but there are many other things that have to be factored into camera choices like post workflows (software and hardware), internal codecs, etc. Color science is something else we tend to overlook, and we shouldn’t, as certain camera choices will multiply the amount of time you need to spend in post to get them to look like what you’re used to.

So, clearly, there isn’t a “perfect” camera that will meet all our requirements. So the best approach is to consider what we have (budget, lenses, software, hardware, accessories, etc.) what we need, and what we are willing to sacrifice. So, what is “the best” camera package for us, giving our existing gear, ideal requirements and upcoming needs? Now I need YOUR help to figure this one out.

UPDATE 01: Since I wrote the first draft for this article I’ve been hearing highly reliable complains about the FS7 working with lens adapters and Canon lenses. That pretty much kills the Sony package option for us.

UPDATE 02: There are strong rumors that Panasonic will be announcing an updated version of the AG-AF100 at NAB, which apparently would include 4K. That could be a great solution for our full blown cinema camera.

UPDATE 03: Another strong rumor is that Canon will replace/update the 3-year old 5D Mark III with a 4K version. Kinda cool, but it still doesn’t solve our “bells and whistles” camera dilemma.

UPDATE 04: For the past 3-4 weeks I’ve been using the Atomos Shogun (Amazon • Adorama) and I must admit I’m VERY impressed. This gadget not only provides an exquisite 1920 x 1080 ultra sharp (and fairly accurate) image, but it’s main purpose is being a 4K (or HD) recorder via Solid State Drives. The best price/quality I’ve found are these 240GB Sandisk for $146 with a 10-YEAR warranty. Not bad at all.

Something I didn’t consider when getting the Shogun is that now I have XLR options, making the GH4 a much more powerful beast. The provided batteries only last about 30 minutes of recording time. I got this off-brand ultra cheap ($36) set of 2 batteries with chargers and so far they have performed perfectly. To keep in perspective, a single Sony battery costs $199….

UPDATE 05: The Varavon cage for the GH4/GH3 works perfectly with a Metabones Speedbooster. This set up and the Atomos Shogun are making me rethink my camera strategy. Now I can have a very comfortable grip, add a shotgun for run and gun or a monitor/recorder with XLR mics on sticks. Hmmmm this is getting REALLY interesting!

More to come.

Video

On Film Directors and Styles.

According to Woody Allen there are two kinds of film directors: “the ones who have it, and the ones who don’t.”

It is well-known that there are two other kinds of movie directors: the ones who write their own material, like Tarantino, and the ones who adapt, like Alfred Hitchcock or Steven Spielberg. The Coen brothers are crystal clear on this: “We are willing to write for other people, but we would not direct a script that has been written by somebody else.” To Scorsese “the script is the most important thing, but it is not everything. What matters is the visual interpretation of what you have on paper.”

John Boorman believes that “directing is really about writing, and all serious directors write.” But there are extremely serious directors who do not work with scripts, like Wong Kar-Wai. “I write as a director, not as a writer, so I write with images. I start with a lot of ideas but the story is never clear. I know what I don’t want, but I don’t know what I want. The shooting process is the way for me to find all the answers. Sometimes I find them on the set, sometimes during the editing, sometimes three months after the first screening.”

Martin Scorsese has, as usual, something interesting to say about the difference between being a director and a being filmmaker. According to him, a director is “someone who only interprets the script and transforms it from words into images.” A filmmaker is “someone who is able to turn his own or somebody else’s material and still manage to have a personal vision come through.”

From a more technical perspective, we have directors who arrive to the set knowing exactly what they are going to shoot, with how many cameras and which lenses (like the Coen Brothers) and there are others who arrive with simply an idea and then follow their gut instincts (like Woody Allen).

When it comes to directing styles there are also antagonistic approaches. Some directors watch the actors rehearse and then decide with their DP where the camera should be, and how many shots will be needed. Fellini is a prime example of this approach. Scorsese disagrees: “you need to know where you are going and you need to have it on paper.” But some directors do the exact opposite. They walk around the set, decide where the camera goes, where the action will take place, and then ask the actors to accommodate.

Wim Wenders used to spend “every evening painstakingly preparing the next day’s shoot, making detailed drawings mimicking storyboards.” After “Paris, Texas” he has taken the opposite approach, “finding the scene construction in the action, and arriving on set without any preconceived ideas about the shots, and only deciding where to place the camera after working with the actors.”

There are some filmmakers who prefer to edit “in the camera,” such as Clint Eastwood or Hitchcock. Others, such as David Fincher, have no problem shooting 50 takes of a single scene and then figuring it all out later in the editing room over the course of months or even years. Woody Allen’s take on this is “it’s a grave error to start shooting a film with a script that is weak or not ready and think, “I’ll fix it on the set or in the editing room.’”

I could probably add two additional kinds of directors: the ones who make films because they have something to say, and the ones who make movies to find out what they have to say, but that would be a whole different article!

Video

The most popular cameras at Sundance.

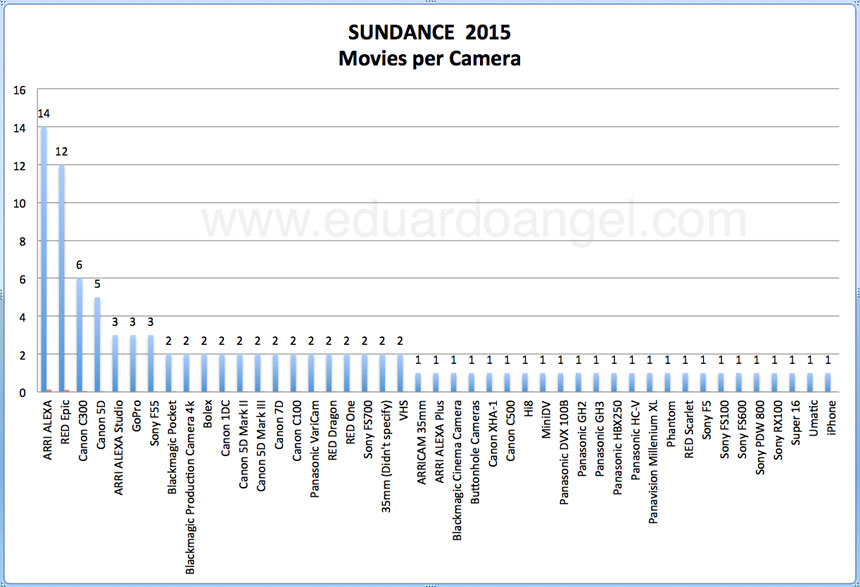

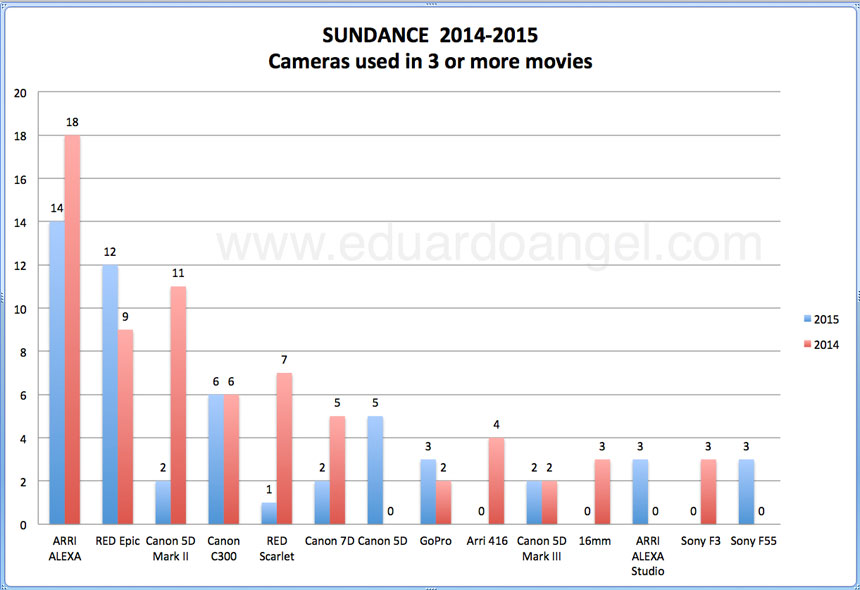

Indiewire published recently the list of cameras used by the filmmakers included in the 2015 Sundance Festival.

The article matched each camera with the film, which was awesome. But I was also curious to see a chart that showed more precisely how many cameras where used and how often. So, I dropped the list from Indiewire into Excel and created this chart.

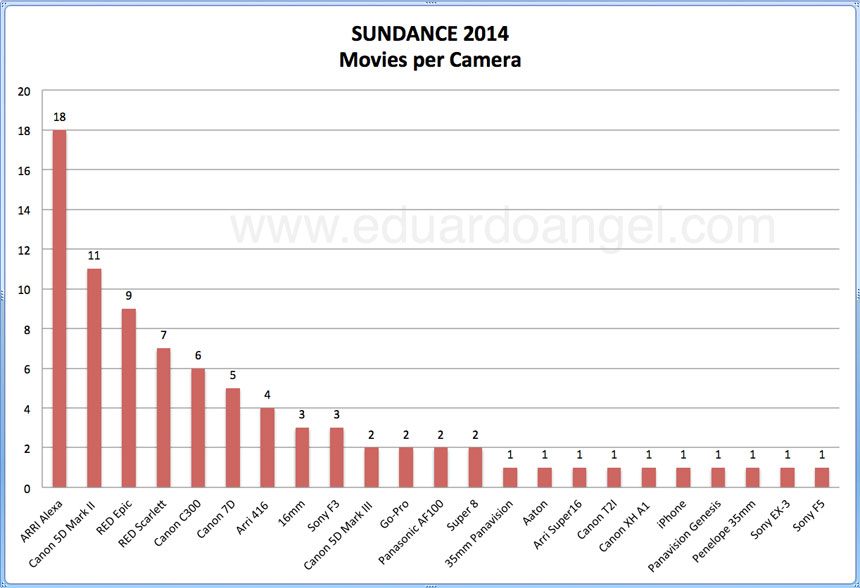

A total of 23 cameras were used in 2014 to shoot 84 movies. In 2015 almost twice the amount of cameras (44) were used to shoot 97 movies. My guess in this discrepancy is that a) Not enough filmmakers in 2014 provided enough or complete information on their cameras or b) the filmmakers in 2015 felt the need to use different cameras on the same movie.

I also wanted to compare the cameras used at the 2014 Festival, so I also created this second chart, again using Indiewire as my sole resource. From the article, it is hard sometimes to tell exactly which camera was used. For example, one of the filmmakers said, “We used Super 35mm with some Red Epic, and a little super 16mm. There is also one Canon 5D shot in the picture.” Which Super 35? And obviously it had to be a Canon 5D Mark II or Mark III as the first version didn’t shoot video. In those cases I only added the Red Epic to the tally.

How can this information become useful? To me it’s simply curiosity, as I believe a great storyteller can be as effective with an iPhone as with any high-end $50K camera. Give ME an Alexa and a million dollars and I still wouldn’t be able to shoot a single frame better than Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki or Roger Deakins.

The camera is just a tool, but these charts could be used as a reference by film programs trying to determine where to spend their camera budgets this year. Or perhaps a film student wanting to work as a DIT or as an AC [insert link http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Film_crew ] can look at these charts and determine, “well, I better get REALLY comfortable with the Arri Alexa and Red Epic in order to get some high-end jobs.” The charts can also be used by filmmakers planning to upgrade their gear.

What I find most interesting about this data is how consistently some of the cameras are used, such as the Arri Alexa, and how one of my go-to cameras, the Canon EOS C100, was used only twice last year and wasn’t used at all on any of the 2015 movies. Another interesting takeaway is how much more diverse the cameras used for Sundance are compared to the cameras used on Oscar nominated movies, where the Arri Alexa also rules, RED and Blackmagic have been absent, and we don’t see a VHS or an iPhone. Or, at least not yet, I should say..